How to explain autism to kids and parents

Updated: December 11, 2023 · 15 Minute Read

Reviewed by:

Amy Gong, Neurodiversity Advocate

Highlights

- Navigating your child’s autism diagnosis can be difficult and full of emotion. It’s okay to process at your own pace and share when you’re ready.

- If you think it will help your child be better understood, or correct unrealistic expectations, it may be a good time to share your child’s diagnosis.

- Using visual aids and simple, fact-focused language is a great way to explain autism to friends, strangers, and loved ones.

- Not everyone will be supportive of your child’s autism diagnosis, and sometimes it may be necessary to set boundaries with people when their expectations or actions may harm your child. This includes even those closest to you, such as family, friends, or your co-parent.

- You are your child’s greatest advocate and protector. It’s okay if you don’t have all the answers, or aren’t able to perfectly explain everything. You can still educate those around you about your child’s autism when you have the energy to do so.

How to explain autism to kids and parents is a common question autism parents ask.

Getting your child’s autism diagnosis can bring on a flood of emotions. You may feel grief, relief, confusion, shock, or any other number of emotions. This is completely normal for any parent navigating a new autism diagnosis. First, you’ll probably want to find out more about autism (our complete guide to understanding autism is a good place to start). Then, you’ll be tasked with figuring out when – and how – to tell people about your child’s autism.

When should I tell people my child has autism?

The simple answer is: whenever you’re ready. Many parents may feel pressured to reveal an autism diagnosis sooner than they’re comfortable with because of judgment from family or strangers, but your child’s autism, beyond being a medical diagnosis, is a deeply personal part of who they are. As your child’s champion, advocate, and protector, it’s up to you when you share your child’s diagnosis. You don’t have to give in to pressure to share your child’s autism diagnosis before you’re ready. Take time to feel what you feel and process the diagnosis yourself, then determine when you’d like to tell others.

When is it the right time to share my child’s autism diagnosis?

When you’re not under pressure. Sometimes loved ones or strangers may put pressure on you to explain or justify your child’s behavior. But you aren’t obligated to share your child’s diagnosis, and you don’t owe anyone an explanation. One exception to this would be if you want to correct unrealistic expectations about your child, such as a loved one demanding your child give them a hug or perform an action you know your child has trouble with (e.g. sitting still during a family photo). The stress of this pressure can make you feel like you’ve got to blurt out your child’s autism diagnosis before you’re ready. But the right time to share is whenever you feel it’s the right time.

Tip: In a situation like that, where you feel your child is being misunderstood but you’re not ready to share their diagnosis yet, you can say something like, “Excuse us for a moment, Timmy and I are going to another room to calm down.” This allows you to respectfully exit the uncomfortable situation, and tend to your child, without compromising their privacy.

When you feel informed and comfortable. It can be frustrating to try to explain your child’s autism when you yourself are still learning. (We’ve been there, we know how that goes!) Words stumble out and you may walk away wishing you’d said this or that differently. When you feel more comfortable explaining your child’s autism and answering questions that may arise during the conversation, that’s an ideal time to discuss your child’s diagnosis. If you’re stressed out, you won’t be able to express yourself in a way you’re satisfied with later.

Tip: We’ve got helpful articles for understanding and talking about autism lingo in our Learning Center.

When the setting is relaxed. A heated debate over Thanksgiving dinner is probably not the best time to share your child’s autism diagnosis! You may want to wait until you’re able to discuss your child’s autism in a relaxed and private setting, especially if the loved ones you’re informing are not particularly knowledgeable about autism. You want to have plenty of time and space to answer questions and lay down boundaries in a neutral setting.

When you have the energy. Discussing autism can be a complicated thing, especially if you’re sharing your child’s autism diagnosis with someone who doesn’t know much about it, or may be in denial. Often, spouses and family members disagree about a child’s autism or the level of support needed. In tricky situations like this, it’s important to make sure you have the energy for the conversation before diving in. If it’s too much for you right now, pause, regroup, and try again another time.

If there isn't the perfect time to share your child’s autism diagnosis, share if...

There are a couple exceptions to the “comfortable and relaxed” rule. You may find yourself in a situation where sharing your child’s autism diagnosis is necessary; in this case, you should share your child has autism if:

You feel it will help your child be better understood. If you think sharing your child’s autism diagnosis will help others understand them better, by all means, go ahead and share. This could be at the store when your child is having a meltdown, or at a family gathering when Grandma Pearl is confused that your child is not responding to their name. Especially if your child is in distress, sharing concisely that your child is autistic can help ease tension in the situation.

Example: Your child hit another child on the playground. “I am so sorry that Bobby hit your son. He is autistic and sometimes has difficulty being gentle, especially when he is sleepy or hungry.”

Example: Your child is having a meltdown in a public place. “My child is autistic and is feeling overwhelmed right now.”

Example: A stranger in the parking lot notices you struggling to get your child back into the car and asks if everything is okay. “Yes, we are okay. My child is autistic and has difficulty moving from one activity to another.”

Example: Your child is at a relative’s house and is breaking things. “Grandma Pearl, I am sorry Bobby broke your vase. Bobby’s autism can make it difficult for him to express things like fear or confusion, so those big feelings sometimes come out as hurting himself, others, or objects around him.

You want to correct unrealistic expectations. There may be times when someone, whether it’s a teacher, loved one, or stranger, may place expectations on your child that they simply cannot meet. This could be a relative who wants your child to make eye contact, a teacher who wants your child to sit still for long periods of time, or your sister-in-law who is frustrated that your child won’t play with the other kids at a birthday party. You know your child’s autism may make certain things difficult for them or that there may be some things they just can’t do. In those instances, it’s okay to correct someone’s expectations or demands placed on your child. Correcting unrealistic expectations or demands is one way you can advocate for your child and reduce the stress on them to act “normal”.

Example: Your child’s daycare instructor has sent home a note because your child isn’t playing with toys or other kids in a typical way. “Chelsea’s autism means she enjoys playing and interacting in ways different from most kids. Usually she prefers to play alone, or work on a separate activity near other kids. Here is a list of items and activities she enjoys at home that you can try with her in your classroom.”

Example: A relative is upset by your child’s behavior at a family gathering and suggests you just need to “discipline” them better. “Aunt Lucy, Chelsea is autistic. She is not being ‘bad’, and she does not need to be ‘punished’. She is overwhelmed and needs time to calm down. We will rejoin the barbeque when she’s feeling better.”

Example: Your child has rejected the meal your new partner prepared. “Part of Chelsea’s autism is that she has difficulty with some foods. It is not personal against your cooking, she is just particular about what foods she can eat.”

Example: An employee at the indoor playground is instructing your child not to climb a piece of equipment. “Hi. My child has nonverbal autism and doesn’t understand what you’re asking her to do. It may be helpful for your staff to learn sign language or post picture instructions on equipment for special needs kids.”

How do I tell people about my child’s autism?

We get it! It can be difficult to explain what autism is and all the ways it affects your child’s life, development, and behavior. Don’t worry if you don’t have all the answers – we are all still learning! Here are some tips for explaining your child’s autism to those in your life, such as family members, siblings, strangers, and more.

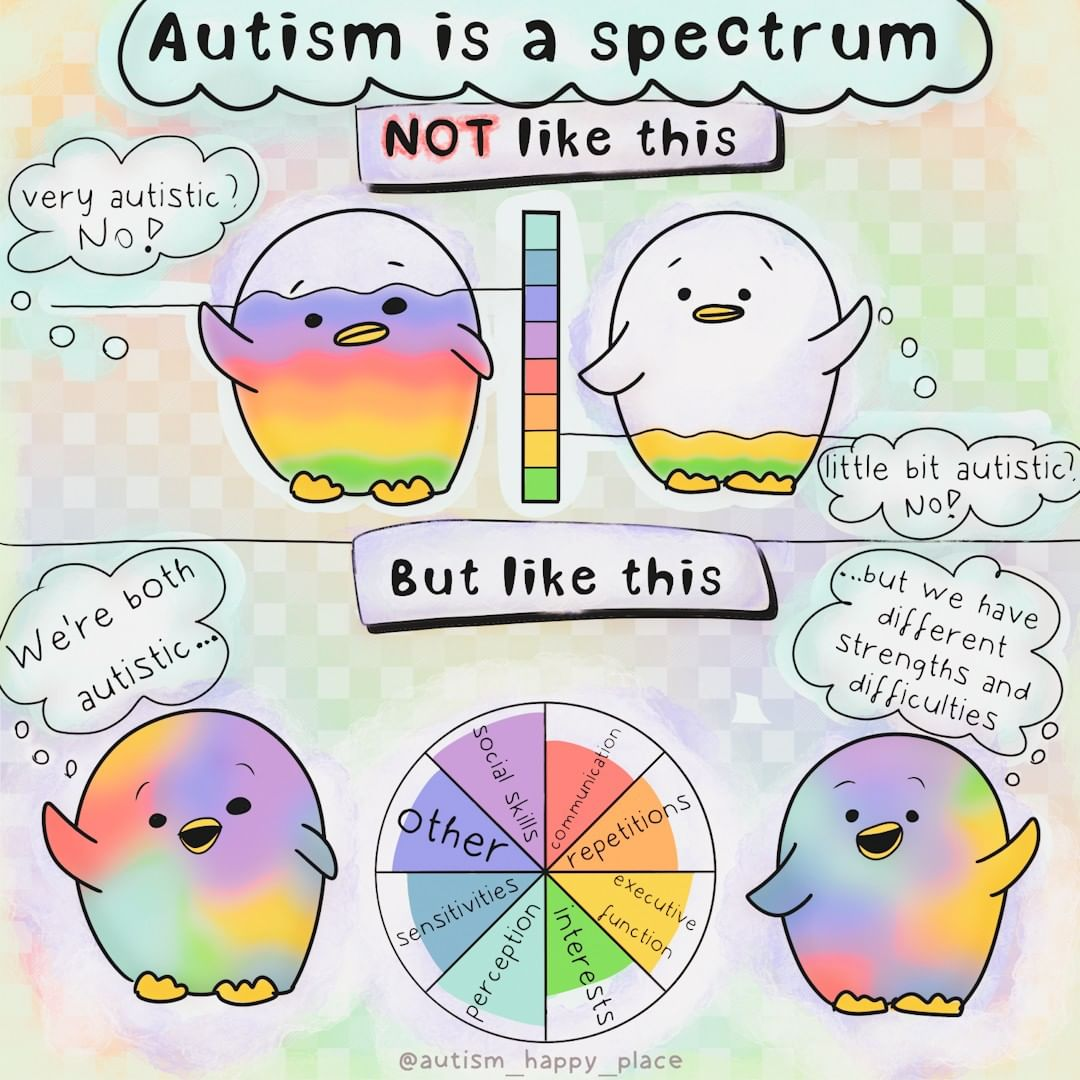

Use visual aids like videos, picture books, and infographics. We love this video by Alexander Amelines for a direct and educational approach. For something more artistic, Disney/Pixar’s short films “Loop” and “Float” use a storytelling approach to share autistic characters. There are also dozens of great picture books that can be used to share your child’s autism with them and their siblings. Another great resource for teaching kids about autism is PBS Kids, which now offers two shows featuring autistic characters, Sesame Street and Hero Elementary. Infographics from trusted sources and autistic creators can be extremely helpful for explaining the nuances of autism to others.

graphic by autistic illustrator @autism_happy_place

Choose simple language and clear points. The language and concepts surrounding autism can be complex and medical in nature, so when you’re sharing your child’s autism diagnosis with others, it’s best to keep it simple and concise. This is especially true if your family or loved ones are not knowledgeable or supportive of autism. Articles from our Learning Center or organizations like Understood.org are a good place to start. We also like this article because it covers a lot of material and incorporates great visual aids from autistic creators.

Example: “Autism is a neurological difference (different brain wiring). It is not a learning disability or a disease to be cured, but it does create a lot of challenges for Timmy.”

Personalize your child’s autism. Often when we speak about autism, we can revert to trying to remember and quote books or articles, forgetting that we as autism parents see and understand our autistic children in ways others do not. When telling people about your child’s autism diagnosis, try using specific examples of your child’s strengths and challenges from everyday life. Helping others pinpoint and recognize the ways your child’s autism makes them unique, contributes to their strengths, and also makes life difficult sometimes, may help them understand it better. It’s important for them to understand that there’s nowhere your child’s autism begins or ends – it’s a permanent part of who they are, and that’s okay.

Example: “Do you remember how upset Abby got when Spot barked? That’s because she is sensitive to loud noises. Her brain becomes overwhelmed by the sensation, and it causes her distress. It’s not that she doesn’t like Spot, it’s just that it’s painful for her to hear him bark. Here are some things we can do next time we visit to make Abby more comfortable…”

Tips for sharing your child’s autism diagnosis with…

.png)

Uninformed or judgmental people. You know that moment when someone says something totally inaccurate about autism, or is critical of your child’s behavior, and you’re not sure how to respond? Well, you can use factual, to-the-point sentences to correct people when necessary. For example, you could say: “No, Abby’s autism diagnosis isn’t sad. Autism is a neurological difference, and it’s part of what makes her so unique. I’m proud she’s my daughter.” Or, “No, actually, we’re not ‘all a little autistic’. Autism is a spectrum, not a scale of less and more. Each autistic person has their own set of challenges and strengths. You’re either autistic or you aren’t.”

Siblings. When telling kids about their sibling’s autism, use language and concepts they can identify with and easily understand. You can say something like, “Jessica needs a bit more help when we go to the store than some kids.” The right time to explain is up to you, but you can begin the conversation as soon as they’re able to understand their sibling is a bit different.

Law enforcement. Use clear, short, factual statements like “My child is autistic and that is why he is not responding to you.” You can also carry an autism identification card, use a medical alert bracelet, and adhere “autistic child on board” stickers to your car window. These things come in handy during emergency situations in which you or your child is unable to inform police they are autistic. However, please keep in mind that your child reaching for their card or communication device can be dangerous when confronted by law enforcement, as they may think your child is reaching for a weapon. (Thanks to ASAN for bringing this to our attention!) It’s best to keep any autism identification clearly visible to avoid this.

What do I do if my family doesn’t accept my child’s autism?

Unfortunately, there are some people who deny the existence of autism, or view a child’s autism in a negative light (such as a behavioral problem, or a disease to be “cured”). While this can be a frustrating mindset to deal with, it’s good to get to the bottom of their concerns and address them with facts, using terms they can understand. Autistic author and educator Chris Bonello has a great guide for speaking with unsupportive loved ones about autism.

Here are some tips for dealing with loved ones who are unsupportive of your child’s autism diagnosis:

Give them lots of opportunities to learn, and remind them that your child will need support that is different to what they may be used to. This can include learning skills and knowledge they aren’t familiar with.

Compare the situation to a more familiar one, to help them understand. Example: “You wouldn’t punish a blind person for bumping into something; autism causes difficulty with certain things and needs to be addressed differently.”

Clearly communicate boundaries. If the loved one will not adjust their actions or expectations, clearly and firmly tell them what you will do (consequences). Example: “If you will not stop playing loud music when Timmy is visiting, we will have to stop visiting.” As difficult as it may be, setting boundaries may be necessary with close family and friends, sometimes even your spouse or co-parent.

When should I set boundaries with loved ones?

If you feel your family member or friend’s behavior is hindering your child’s growth, or if they are not respecting your child’s needs, or are causing them harm, it’s probably time to set some boundaries. Remember, you are your child’s greatest advocate and protector, so treat this like any other situation you’d need to protect your child’s safety.

What do I do if my partner and I disagree about our child’s autism?

If you and your partner or co-parent are not seeing eye to eye on your child’s autism diagnosis, or how to proceed with the resources your child may need, that can be a very stressful situation for all of you. If you aren’t on the same page with them about your child’s autism, try:

Seeking knowledge from experts and other parents. Gather information and digest it together. If your partner or co-parent is resistant, there may be a larger communication issue.

Prioritizing maintaining your relationship. There may have been underlying relationship issues that existed before your child’s diagnosis came up. It’s important not to neglect your relationship. Keeping yourselves in a healthy, loving place will make coming to a resolution about your differing viewpoints more doable. Spend time together, seek out couples’ therapy, individual therapy, or both, if necessary. Remember, you’re on the same team.

We’d like to give a special ‘thank you!’ to the experts who contributed their wisdom to this article: Christian Vinceneux, coach for neurodiverse families and former occupational therapist; Lilyan W.J. Campbell, LMFT, BCBA; and Jami Lynn, Marriage and Family Therapist intern.

Get our best articles delivered to your inbox each month.

We respect your privacy.